It’s 98 degrees on a June day in Austin, Tex., but the humidity makes it a balmy 118. I’m sitting on a shaded bench waiting for Alan Graham, founder of Community First Village, a 51-acre master planned development in the northeast part of the city providing housing and support for people who have struggled with chronic homelessness. The successful program is quickly becoming a model for the nation.

A former real estate investor and developer, Graham’s journey began when he volunteered at his church handing out bagged lunches to the homeless and realized that being mobile could increase the number of meals served. He bought a green minivan, which turned into a fleet of food trucks. That led to his first nonprofit, Mobile Loaves and Fishes, which has served more than 5.5 million meals since 1998. As Graham got to know the people he was helping, he saw the biggest thing lacking in their lives besides a home was community. He also realized that for less than $5,000 he could buy a used RV, so he bought several and began dreaming of building an enormous RV park that would not only provide housing but also an extended family support system. His dream became a reality three and a half years ago with phase one of Community First Village, which provided RV and micro housing to 170 formerly chronically homeless residents. In the fall of 2018 they broke ground on phase two, which includes an additional 24 acres, 310 housing units (including the nation’s second 3D-printed tiny home), a 20,000-square-foot medical facility, and more room for organic farming. Set to open in February 2020, phase two will bring the total number of people housed to 500, roughly 40 percent of Austin’s homeless population — and it’s all privately funded.

Park mobile homes, delivered fully furnished for $36,000, rent for $430.

A DIGNIFIED INCOME AND ACCOUNTABILITY

A golf cart pulls up, driven by a man with a neatly trimmed silver beard. He’s wearing a baseball cap and khaki shirt emblazoned with the Mobile Loaves and Fishes logo, and a silver crucifix pendant around his neck. “I’m Alan Graham,” he says, tipping his sunglasses. “Hop in.”

He’s holding a report titled, “San Francisco’s Homeless Crisis: How Policy Reforms and Private Charities Can Move More People to Self-Sufficiency.” I ask where he got it. “Someone from up where you live,” he says in his Texas drawl. “I get this stuff from people in the Bay Area all the time.” I ask him if anyone from the Bay Area has visited. “We get ’em, sure,” he says. “The problem is politicians are afraid to let go of something they think they own. It’s about innovation and the government isn’t very innovative. On the federal level, [the Department of Housing and Urban Development] is all about ‘housing first,’ but can you imagine a tech company leaning on just one solution? Housing is a piece of the puzzle, but it’s not going to get a city like San Francisco out of this. That $12.5 billion they say it will take? That’s not going to get them out of it, either. It’s a human issue; it’s about the government admitting they can’t do this — money and housing alone won’t solve homelessness, but community will.”

The street signs at Community First Village are all about the positive.

As we zip along the grounds, Graham points out the various parts of the village, including a medical clinic, an addiction treatment center, a barbershop and salon, and a dog park. “We love animals here,” he says. Early on they partnered with Austin’s famed Alamo Drafthouse to build the Community Cinema and Amphitheater, which hosts free movies all year for anyone who wants to attend. “This is one of the ways our Community First neighbors earn a dignified income,” Graham says. “They work in the Community Grille making food, they serve concessions, and they earn 40 percent of the sales.”

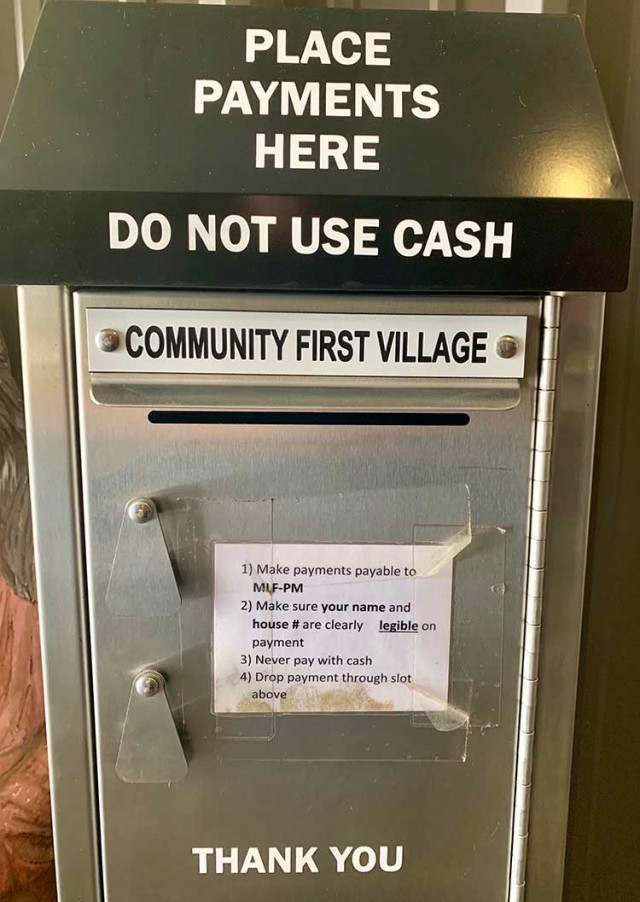

One of the many things that sets Community First Village apart from the traditional homeless shelter model is residents can stay as long as they want, but they must pay rent, which covers roughly 40 percent of the $6 million budget. “If our neighbors miss rent, they’re asked to leave, but it doesn’t happen very often,” Graham explains. While he doesn’t like to throw numbers around, Community First has a retention rate of around 86 percent.

Rent at Community First Village is mandatory.

“We have three rules here: You must pay rent. You must obey criminal laws. And be mindful you live in a community — if your dog poos in the yard, you must pick it up. You see how clean and orderly it is? If you want to live like a pig, go live in the woods.”

The reason people don’t pay their rent usually has to do with drug or alcohol addiction. While Community First makes treatment options readily available, sobriety isn’t required. “What we are doing is harm reduction. We’ve done four studies, and there’s an 80 percent drop in drugs and a 60 percent drop in alcohol when people come here. To us that’s a tremendous victory. If you’re the only victim, and you want to trash your body, you can do it ’til the cows come home. But if your use spills into the community, we will get involved. We don’t want your dealers here. We will stop that. If you’re stealing from me to feed your habit, we’re gonna have a problem. If you don’t make it to work and pay your rent, you’re gone.”

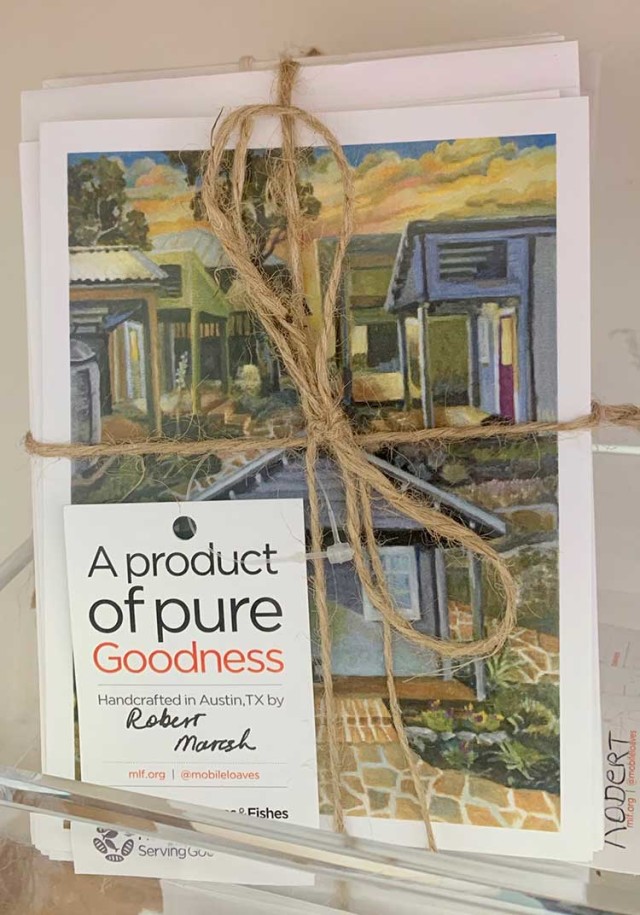

Art by residents is for sale in the Community Market.

AIRBNB MEETS TINY TOWN

Near the entrance we stop at a row of trailers and tiny homes called the Community Inn, where people can make reservations for a stay via Airbnb. “They’re always booked,” Graham says proudly. “Sometimes folks come to experience what we’re doing here and sometimes they have no idea where they are.” Visitors range from attendees of Austin’s renowned South by Southwest festival to those wanting a weekend getaway, and some are so transformed by the experience they become “missionals” — people who aren’t homeless but choose to rent a micro home or RV and become part of the community. Current missionals range from retired attorneys to tech executives who commute daily from the village to work.

We cruise through the micro home area, known as Tiny Town, where each unit is connected to single occupancy showers and restrooms as well as outdoor kitchens with barbecues. Homes rent for $225 to $375 per month (air conditioning is an additional $35). The smoky, luscious aroma of Texas barbecue wafts through the air as we pull up to a home where three men are sitting on the porch. “Hey Butch, whatcha cooking?” Graham asks. “Ribs,” Butch says through a big grin. “You need to come by later and have some, Alan.” Graham rubs his beard thoughtfully. “We need to have a barbecue competition,” he says, but the neighbors are way ahead of him. “Already happenin’ on Aug. 7…” An impromptu brainstorming about categories begins (“You gotta have ribs, brisket, and chicken,” Butch says, while Graham and the others pull for pulled pork). “Come by the office tomorrow,” Graham says. “I’ll buy the trophies.”

Tiny Town neighbors relax while testing their ribs recipe for a community barbecue competition Photo: Susan Dyer Reynolds

PRACTICE WHAT YOU PREACH

It’s apparent the neighbors know Graham well and the connections run deep. I ask if he’s at the village every day, as we arrive at a charming navy blue micro home with cream-hued shutters. “I’d say so,” he says, inviting me up the steps. “I live here.” The porch, dotted with pink and red flowers and shiny green foliage, leads to 399 perfectly appointed square feet that makes me wonder why anyone needs more. Graham and his wife Tricia obviously agree — it’s a significant downsizing from the 3,000-square-foot home in Westlake Hills where they raised five kids and resided for 35 years.

As he shows me around, Graham reflects on a meeting he attended at Austin’s City Hall the night before. “They overturned three ordinances that criminalized homelessness and approved a new 100-bed shelter. The community was mostly for it, and I think our fingerprints are on this. We’re showing what can be done when a city, a community, comes together. The problem is always NIMBY. In San Francisco, they vote the most liberal agenda on the planet, but when it comes to welcoming the broken and battered into their neighborhood it’s ‘Oh no! It’s one mile from an elementary school and that’s far too close.’ The progressives have become the elitists.”

I ask if there are differences in the populations at Community First versus San Francisco. He shakes his head no. “We serve the chronically homeless — like the Tenderloin in San Francisco — and they’re redeemable. I believe 80 percent of the folks in the [Tenderloin] are redeemable. Then you’ve got the drug addicts and the severely mentally ill. We’ve got people off the rails in a giant way, and they need a different level of care. I know that reality — my mother was profoundly mentally ill, and I had to institutionalize her when I was 18. That has to be an option.”

Artist Robert Maresh shows one of his paintings, for sale in the Community Market. Photo: Susan Dyer Reynolds

FARMERS, ARTISTS, AND AUTO MECHANICS

Back in the golf cart, we cruise by the farm where we see a herd of goats (“Neighbors make soap, and soon we’ll be certified for milk”) and the beehives (“We had the honey tested and a good amount of the pollen came from Cannabis plant”). Free-range chickens produce dozens of eggs per week; there are hundreds of fruit and nut trees, an acre of organic vegetables, and a tropical geodome. Farming is another job source for neighbors, Graham says, and the entire village can have as much food as they want.

At the Community Market, Graham proudly shows off the crafts and artwork for sale created by neighbors like Robert Maresh. “He’s a gifted artist,” Graham says as Maresh shows me one of his paintings, a stunning swirl of blues and greens woven into images of a shaman, cacti, and horses.

Next we visit the pottery studio where we meet Ute as she works on diminutive, incredibly detailed pieces for a chess set someone commissioned her to make out of clay. Originally from Germany, Ute says she and her husband, Michael, were homeless for 10 years due to a string of bad luck and lost jobs. “Mobile Loaves had a trailer as an art studio and we would go there and paint. They would take us to church markets on weekends so we could sell our art and make money. We’ve been living here at the village since 2017. We work, we have a home — we feel secure, and that’s so important. …”

Artist Ute holds one of her clay figures.

Clay pieces for a chess set by Ute, commissioned by an Austin resident.

When we reach Community First Car Care, Graham notes Toyota approached him and offered to set up the shop and train neighbors to provide oil changes, inspections, and auto detailing. Nearby Goodness Press offers screen-printing services to individuals, volunteer groups, and businesses. At the blacksmithing shop, I ask if people bring their horses for shoes. Graham breaks into a belly laugh. “You really are a city girl,” he teases. “They make art objects and iron gates . . . things of that nature.”

As the afternoon winds down, a welcome breeze blows through the trees. We stop at the center of culinary operations, run by Graham’s son, Keaton, who has a degree in petroleum engineering from the University of Texas but says he always had an affinity for cooking. They make the food for movie nights, but have been expanding: the wholesale bakery is taking orders from outside, including homemade brioche buns and birthday cakes, and they recently catered a $100-a-head party. “There’s a pride that happens when neighbors see the happiness from a client who isn’t expecting such good food to come from the formerly homeless,” Keaton says. His dad nods. “Everyone thinks the homeless are helpless; that they’re the dumbest population, but I tell people that in an Armageddon you better make friends with them cuz they know how to get things done, not the rich people living in condos.”

Combined, Community Works micro enterprises have produced $1.1 million of dignified income for neighbors in the Community First economy. The programs also enable volunteers to serve alongside residents, helping them build new skills while forging enduring relationships.

To get to that level of success, however, stability is critical — starting with a roof over your head. As we pass a brand-new mobile home, I ask Graham if it’s possible to build housing in an expensive place like the Bay Area without spending six figures per unit. “This model comes delivered for $36K,” he says. “Fully furnished, it’ll rent for $430 plus electric and propane. A 320-square-foot RV is $410. You’ve got to be creative.” Graham, who takes no money from city, state, or federal governments, believes politicians are not equipped to solve the homeless crisis. “For them it’s all financial, but it needs to go from the transactional to the relational. Profound, catastrophic loss of family is the number-one cause of homelessness … everything else is a result of those past traumas, and the loneliness and desperation that settles in. The money is there in San Francisco times a billion compared to Austin, but not the vision or the passion or the focus. At the end of the night, we all need to be tucked in by another human. When the people with the money get that, they’ll get it in a big way.”

E-mail: [email protected]. Follow the Marina Times on Twitter @TheMarinaTimes and like us on Facebook @MarinaTimes.