We have this expression, Christy and I: We don’t wake up for less than $10,000 a day.

— Supermodel Linda Evangelista to writer Jonathan Van Meter in a 1990 article for Vogue magazine

That now infamous quote from Linda Evangelista came at a time when supermodels ruled the world. During the 1980s, the glamorous Amazonian cat-walkers, including Cindy Crawford, Christy Turlington (referred to in the quote), Naomi Campbell, and Claudia Schiffer, made ridiculous sums of money to do ridiculous things — and it went to their heads. Several of the elite group even joined forces to create the Fashion Café, a takeoff on Planet Hollywood, and eventually lost their designer shirts on the project (I guess people weren’t interested in a restaurant from the minds of women who live on a diet of champagne, rice crackers and cigarettes).

As the 1990s unfolded, fashion designers began dumping supermodels as their human clothes hangers in favor of movie starlets, and the public, as it always does, got bored and moved on to the next big thing — a revolutionary concept called The Internet. Like the dinosaurs before them, the reign of the supermodel was over. Today, you can find some of them on late-night infomercials hawking skincare lines or on really bad America’s Next Top Model rip-off reality shows.

The 1990s, of course, ended with the dot-bomb heard round the world as the web’s version of supermodels garnered unrealistic valuations based on questionable, unproven businesses that were unable to make money nearly as fast as they spent it. Webvan.com burned through $375 million in three years and went from a $1 billion valuation to bust within a year; eToys.com had $247 million in debt before dying off in 2001; GeoCities, purchased by Yahoo for $3.6 billion in January of 1999, was shut down in 2009; Pets.com went from IPO to liquidation in 268 days after burning through more than $80 million on advertising and marketing; and Myspace (the Facebook of its day), purchased in 2005 by Rupert Murdoch’s News Corporation for $580 million, sold for $35 million just five years later — a fraction of the $100 million Murdoch was seeking.

Fast-forward to April 2012 and it seems we have forgotten about the fall of 1980s’ supermodels and 1990s’ dot-coms as Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg purchases Instagram, an unprofitable, 16-month-old photo-sharing app, for $1 billion. Perhaps comedian Jimmy Kimmel summed the deal up best: “A billion dollars? Unless they have some faded, washed out picture of Mark Zuckerberg killing a hooker, it doesn’t make sense!”

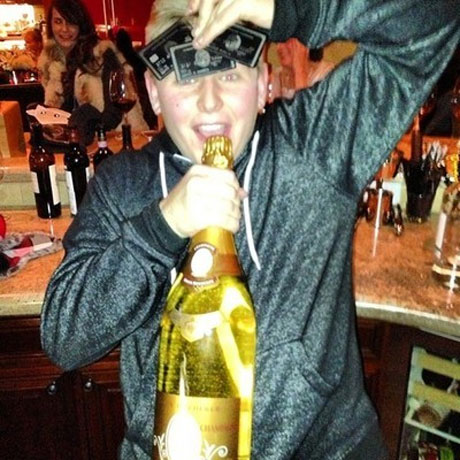

The deal was like hitting the lottery for those onboard the early Instagram train: for less than a year-and-a-half’s work, 27-year-old founder and CEO Kevin Systrom took in a cool $400 million and co-founder Mike Krieger got $100 million; venture capital firms and individual investors split $400 million; and the final $100 million was split by Instagram’s 12 remaining employees. Because the deal was mostly stock (a rumored 70 percent), the billion fell to a mere $715 million after Facebook’s fumbled IPO, but the kids of Instagram still got rich. In fact, the website dailyfunlists.com decided to show us — in photos, appropriately enough — just how rich they are in a slideshow titled, “Rich Kids of Instagram Part 2” (darn, I missed Part 1). The 12-photo series starts with a Rolls Royce kissed by the sunset, followed by a group of sweaty, shirtless guys with the hairless, nubile bodies of 12-year-olds guzzling from gargantuan bottles of Veuve Clicquot; a smug blonde guy in a black blinged-out glitter hoody holding up an equally gargantuan bottle of Cristal and plastering American Express Black cards to his forehead; and another guy being pulled through the snow in a sled hitched to a neon yellow Ferrari. I could go on, but I don’t want to make you lose your lunch.

One year later Facebook has yet to figure out a way to make money off the photo-sharing app, but that hasn’t stopped the rich kids of Instagram from partying like it’s 1999. Because most of them were in diapers when $9,000 a day couldn’t rouse Linda Evangelista and in junior high when 1999 rolled around the first time, they likely have no recollection of those cautionary tales of the way insta-success and arrogance often lead to irrelevance and oblivion.