Recently I had lunch with Carl Nolte, who writes the Native Son column for the San Francisco Chronicle. Carl is a young whippersnapper compared to me, but we find common ground when we talk about the history of our city. We decided to don neckties and sports coats and go downtown to Sam’s Grill, which had just reopened after an unsettling time when we thought it might be gone forever.

Carl decided to give the Alaskan cod a vote of confidence and proclaimed it well deserved, flaky, and flavorful. I opted for the fried oysters and some creamed spinach. They were excellent.

From our choice of restaurants, you might surmise that Carl and I put value on the traditional. We do. And after lunch, with our neckties still firmly in place, we got to reminiscing over a second glass of Sauvignon Blanc — just two old San Franciscans thinking about then and now in their favorite city.

Carl posed a question: Can the old-time San Francisco with its middle-class values (where he and I grew up) co-exist with the new San Francisco and the new San Franciscans? He answered his own question in the affirmative but said it would be a balancing act. I agreed. We parted, loosening our neckties, and deciding our next lunch would be at another classic, Capp’s Corner in North Beach.

Since the Sam’s Grill lunch with Carl, I’ve been reflecting on our conversation and have developed this column on the then and now of San Francisco.

THE INSTANT CITY

Right from its early days, the raw-boned, fog-bound town called San Francisco had a high degree of sophistication that belied its edge-of-the-continent isolation. The Gold Rush in 1849, the discovery of Nevada’s Comstock Lode of silver in 1857, and the completion of the Transcontinental Railroad in 1869 had turned this tiny village into an instant city. Suddenly San Francisco became a western metropolis with worldly tastes and enthusiasms.

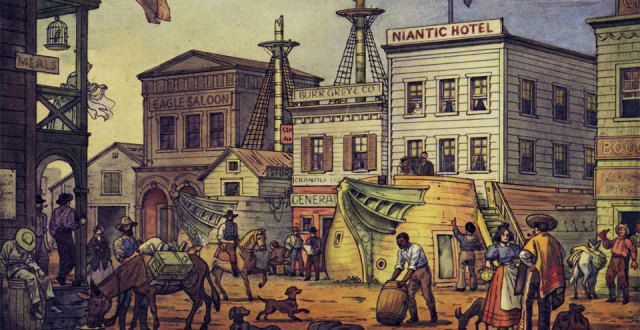

Early San Francisco was rambunctious and disorderly. It was overrun with a motley crowd of adventurers — both men and women — from all over the world. Along with the gold seekers, get-rich-quick ruffians and con artists came merchants, farmers, clerks, clergy, bankers, doctors, poets, prostitutes, lawyers, sailors, socialites, salesmen, speculators, and just plain seekers of the good life. Some just liked the climate and wanted to live in the European-styled instant city by the Golden Gate. By 1875, the population of San Francisco was 190,000. In 1900, it was 350,000.

PARIS OF THE PACIFIC

Obviously, all of these independent mavericks wanted to get rich, but they shared other desires as well. They sought good food and drink and good entertainment. Those who did not occupy tents or jerry-built wooden shanties lived in boarding houses and hotels, which sprang up all over town. And suddenly there were restaurants to feed them. San Francisco became a city that eats out. Diners had money in their jeans and expected the best. That’s what they got. Early San Francisco chefs tended to be Frenchmen from what were already fine restaurants on the country’s East Coast. Some said San Francisco was on its way to becoming the Paris of the Pacific.

Not only were there skilled chefs here but the raw materials for their art was plentiful — oysters, crab, and many kinds of fish were to be found in the bay and nearby rivers. Game roamed the adjacent wilderness. Valleys to the north and south provided vegetables and fruit. The Hungarian Count Agostin Haraszthy brought European wine grape cuttings here from France in 1861. But even earlier knowledgeable San Franciscans were drinking French wines that came around the Horn by sailing ship, or a bit later by transcontinental rail.

THE POODLE DOG

One of the first San Francisco restaurants was the Poodle Dog, which opened in 1849. The restaurant’s true name was Poulet d’Or (“golden chicken”), but it is widely believed that unschooled miners corrupted the name thinking it sounded like “poodle dog.” Soon the owners adopted the corruption and even installed a white poodle. But if many denizens of the instant city did not understand the French language, they did understand the language of French cuisine.

And there were other reliable temples of gastronomy in those days. Perhaps the most famous was Delmonico’s, which was serving elegant French food here in 1850. (The original Delmonico’s opened in New York in 1837.) Other San Francisco old-timers are Tadich Grill, which dates to 1849 and Jack’s, which opened in 1864. Sam’s Grill (the inspiration for this Back Story) opened in 1867. The Cliff House (1863), Old Clam House (1861), the Palace Hotel with its incredible, stained glass-enclosed Garden Court (1875), Schroeder’s (1893), and Fior d’Italia (1893) are others.

ALONG CAME SHAKESPEARE

And while these citizens of the Paris of the Pacific were enjoying the pleasures of the table, there were many other entertainments to occupy their time. Not only blackface minstrel shows and raucous comic skits and pantomimes (even a female impersonator, James Evrard in 1850) performed in saloons and dance halls like the Bella Union at Washington and Kearny Streets, but more refined and traditional entertainment was popular as well. In 1850, the Jenny Lind Theater opened in Portsmouth Square. Before it burned down a few months later, it featured Shakespeare’s Twelfth Night — a comedy, you will recall, in which a male actor, playing a woman, pretends to be a man. In three years in the 1850s, 14 plays by Shakespeare were produced in San Francisco.

While brothels and honkytonks dominated the performing arts of the times, the largely male population of the town soon began patronizing productions of more classic offerings. Theaters and opera houses sprang up, seemingly overnight. The first opera performed in San Francisco was Vincenzo Bellini’s Somnambula in 1851.

In the 1850s the art of dance was represented by Lola Montez, who did her famed spider dance act (the spider was believed to be crawling about beneath her flesh-colored costume) and somewhat later by the free form, freethinking Isadora Duncan, famous for being famous.

The birth of the San Francisco Symphony Orchestra traces back to 1881, when the Philharmonic Society presented a well-received series of concerts offering pops of the day and works by Mozart or Handel.

THE SAN FRANCISCO GOOD LIFE

The mining camps in the Sierra foothills were the Silicon Valley startups of the time. And while life panning gold could be rigorous, the miners dined on top-quality foodstuff from San Francisco. Oysters, fish, game, and vegetables arrived by riverboat up the Sacramento and American rivers and then overland by oxen-pulled wagons.

Booze was plentiful, and so was entertainment, both raucous and refined. Many of the top entertainers of the time journeyed to the camps to perform. Famed Shakespearean actor Edwin Booth and child singer-dancer Lotta Crabtree played the camps and were paid handsomely.

There were gold miners who had staked claims and were doing well and preferred to live in comfortable San Francisco. They journeyed to and from the gold fields in what today would be Google buses — horse and buggy or by river steamboat to San Francisco Bay.

Many miners, merchants, and professionals the Gold Rush attracted later became part of the San Francisco community where they could not only participate in the good life — but also get their laundry done. They involved themselves in civic affairs and paid big bucks (or a lot of gold nuggets) to build McMansions.

Those not politically oriented set up shop as doctors, lawyers, or merchants. Some did what Silicon Valley techies do today: they got into politics. One miner, Andrew Jackson Bryant, made a poke and later became mayor.

And that’s the way it was.

HAS SAN FRANCISCO CHANGED?

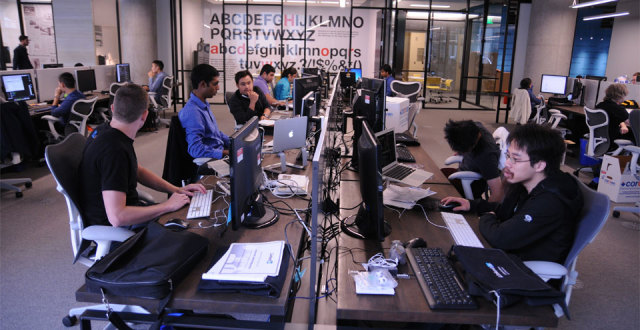

These days San Francisco’s new citizens — whether they’re techies or some other types of end-of-the-rainbow seekers — are not unlike those who followed their dreams west in those early days. For every roughneck miner and adventurer there were smart, creative, self-motivated, self-starters: merchants like Levi Strauss who changed the way the world dresses; businessmen like railroad barons Collis P. Huntington, Mark Hopkins, Leland Stanford, and Charles Crocker; bankers like A.P. Giannini, who financed San Francisco after the 1906 earthquake and fire; publishers like Sam Brannan who ran San Francisco’s first newspaper. And Charles James Brenham, a ship’s captain who ferried miners from San Francisco to Sacramento.

Now, just as they did then, ambitious folks come here for the food, entertainment, the good life, and to get rich. Has San Francisco changed so much? No, I don’t think so. Can this diverse group coexist? Yes, I do think so.