Currently on display at the Legion of Honor is a historical presentation representing five centuries of pastels from 16th-century Europe to the present day. Through rarely seen holdings from the museum’s Achenbach Foundation for Graphic Arts and prominent Californian collections, the 80 works in the exhibition trace the technical evolution of the medium.

Pastels were developed in the early 16th century. At that time, European artists incorporated natural colored chalks in their preparatory studies. The fabricated pastel stick became popularized in the 17th century, especially in portraiture, due to its velvety effects in re-creating skin tones.

A DUAL NATURE OF DRAWING AND PAINTING

“In a singular combination, pastels convey the immediacy of a drawing, the appearance of a painting, and the matte finish of a fresco,” said Furio Rinaldi, curator of drawings and prints at the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco.

This exhibition focuses on the materiality of pastels. Nearly unchanged since the Renaissance, pastels are composed of finely ground pigments, a dry filler (kaolin or chalk), and a binder (traditionally a vegetable gum). In chronological order, the exhibition examines the technique from its earliest usage in portraiture. The Venetian artist Rosalba Carriera (Portrait of a Lady as Diana, ca. 1720) brought the medium to new levels of popularity. So popular were her pastel portraits that she was admitted into the Académie Royal in Paris in 1720 despite a statute against admitting women.

THE ERA OF IMPRESSIONISM

When stable colors of green pigment became widely used, pastels expanded beyond portraiture and into landscape and still life. Key works from the 18th century include Albert Bartholome’s portrait of his nephew Prosper (Prosper, The Artist’s Nephew in Bed, 1882); the monumental panel by Edmond-François Aman-Jean, Les Confidences (ca. 1898); and Jean-Francois Millet’s The Sewing Lesson (ca. 1860), which is on rare loan from the Crocker Art Museum. Illustrating a mother and daughter sharing domestic duties, the subdued interior and bright exterior light of The Sewing Lesson are blended with pastel and Conte crayon (a fabricated stick made of graphite, clay, and charcoal).

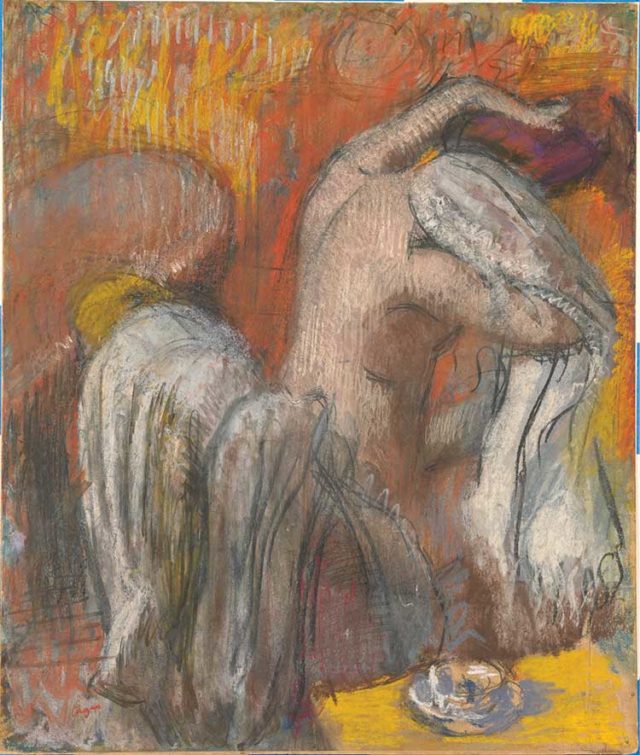

Impressionism saw a resurgence of pastel because it was more portable and conducive to work en plein air. Executed more quickly than oils, pastels could be produced with greater immediacy, limiting the time for posing and observation. This allowed artists to capture a rapid, loose style both painterly and sketch-like, all in vibrant colors. Two late masterpieces of Edgar Degas, Femme s’essuyant (Seated Bather Drying Her Neck, ca. 1905–10) and Dancers (Danseuses, ca. 1895) exemplify color and line in a single gesture.

PASTEL IN THE 20TH CENTURY

Artists in the 20th century pushed the limits of the medium by experimenting with abstract subject matter. Odilon Redon’s Orpheus (ca. 1905) presents the tragic hero of Greek mythology suspended in a field of deep blue with strokes of yellow, hovering ghostlike over his lyre. Renowned for his divine musical talent, Orpheus’s head was preserved upon his death so he could continue to sing forever. Salvador Dali takes the Freudian topic and applies it to one of his Surrealist landscapes in Oedipus Complex (1930). High contrast light and deeply hued shadows frame a biomorphic shape whose multiple orifices bear the words “ma mere.” An unsettling detail, a swarm of ants representing decay, emerges from the face of the object.

POSTWAR AND CONTEMPORARY CALIFORNIAN ARTISTS

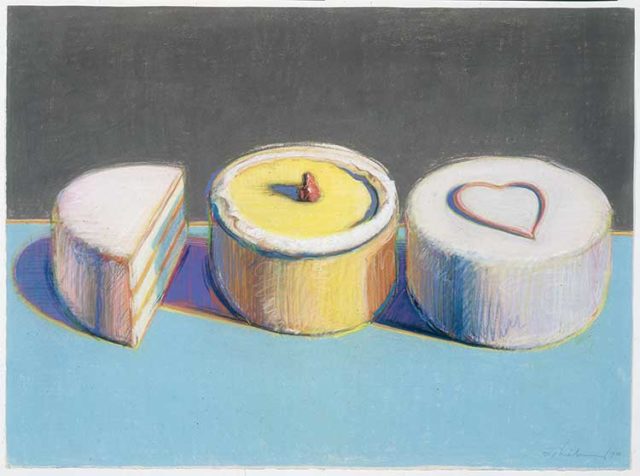

Many contemporary artists are represented in this final grouping, including several pieces by Wayne Thiebaud. In Two and One-Half Cakes (1972), the geometry of cakes as everyday objects is a part of Thiebaud’s playful trademark, and the vivid yellow represents dyes used in the confectionary food industry. In the final galleries, visitors will see the monumental drawing by Enrique Cagoya named Thesis/Antithesis (1989), and an enigmatic trompe l’oeil by Claudio Bravo (Package, 1967). Executed with a polished and photorealistic technique, Package is a mystery, leaving the viewer wondering what secret object resides behind the paper image.

ADDITIONAL PROGRAMMING

A series of lectures and events correspond with this exhibition, including an onsite conversation on Nov. 6 with Xavier F. Salomon about Carriera’s pastels and the pathway she created for women artists. Also, a virtual event will take place on Dec. 1, “Making Pastels with Alex Warren,” owner of Sinopia Pigments. Warren will demonstrate how pastels are made from scratch, and will give an introduction into types of glues, pigments, and chalks.

‘Color into Line: Pastels from the Renaissance to the Present’: Tue.–Sun., 9:30 a.m.–5:15 p.m. through Feb. 13, $25, Palace of Legion of Honor, Lincoln Park, 100 34th Ave., 415-750-3600, famsf.org

Sharon Anderson is an artist and writer in Southern California. She can be reached at mindtheimage.com.