After months of increasing political heat generated by concern about a growing lack of affordability in San Francisco, Mayor Ed Lee addressed the issue with a plan to retain and increase affordable housing in the city, as well as lobby Sacramento to make changes to the state’s eviction law, the Ellis Act. The federal government even kicked in some money. But will any of that be enough?

While residents await clues about how those plans will be implemented, the temperature has continued to rise, with activists disrupting business transit programs and public hearings alike. Lee, who has staked much of his reputation as mayor on his stewardship of the city’s explosive growth coming out of the Great Recession, is likely going to find that the next phase of his time in office will be judged by how well he shepherds the city through the dislocations caused by that fast growth.

In late 2013 and early into the new year, housing prices began to moderate a little in the city, but there has not been a dramatic or noteworthy decline in prices. They remain at lofty levels.

Consider: In late January, HGTV’s reality series House Hunters featured a retired stockbroker who wanted to move from down on the peninsula into the city. His budget for a home was $3–$4 million, which, he said with a straight face, doesn’t go that far in a city like San Francisco. By the end of the episode, he had looked at homes in Cow Hollow, Noe Valley, and Ghirardelli Square, finally settling on a $3.2 million condo in the last of

those locations.

That story includes much of what is driving the affordability debate in San Francisco. A multimillionaire wants so much to come into the city that he “settles” for an expensive condo (with, admittedly, an awesome view of the bay). Meanwhile, new two-bedroom apartments are renting for $3,600 or more, and low- and middle income residents are finding it impossible to get apartments to rent or homes to buy within their budgets. And note that the stockbroker does not ride a corporate bus to work at Google, which has become the scapegoat of many of the activists.

Against that background, Mayor Lee has presented his plan to retain the city’s middle class and to ensure that he is not made the new scapegoat come reelection time.

THE PLAN

Mayor Lee made the proposal in his January State of the City speech, laying out a seven-point plan that would construct or rehabilitate 30,000 new homes in the city, with at least one-third of them being permanently affordable to low-income households (those earning less than 80 percent of the median income, or $77,700 for a family of four) and moderate income (less than 120 percent of median income, or $116,500 for a family of four), and a majority of them targeting the middle income category (which, in San Francisco, means a family of four with income up to $145,650, which would be a princely sum in most parts of the country).

The plan’s elements include reform of the eviction process; stabilization and protection of at-risk rent-controlled units, using rehab loans and a new program to permanently stabilize rent rates for these units; revitalization and rebuilding of public housing units; doubling the down payment loan programs, which particularly can help middle class homeowners, including on land under public control; building more affordable housing, relying more on the private sector to share the cost burden; building more market-rate units, especially rental units, to deal with the pent-up demand from years of inventory constraint and the resulting price spikes; and easing construction of new housing by boosting staff in city departments involved in housing, streamlining the process to speed it up, and boosting neighborhood infrastructure.

There’s something in that plan for everyone, including activists seeking protection of existing units, developers seeking to build, new residents of all incomes, and existing homeowners who don’t want their home values to decline. The mayor will seek to involve housing advocates, developers, property owners, and others in a task force to study, develop, and implement the plan.

Critics will be watching closely to see over time how many of those 30,000 units are new and how many are rehabilitated. Rehabbed units can be very important; rehabilitation is often a time when a lower-priced unit is spruced up at great cost and then put back on the market at a high price point. But the devil will be in the details. What will constitute “rehabbing”? Will that just be used to count some affordable housing units that got mold remediation and a new coat of paint and that were likely to remain affordable anyway? Or will it actually preserve affordable units that were at risk of being torn down or otherwise leaving the affordable inventory completely?

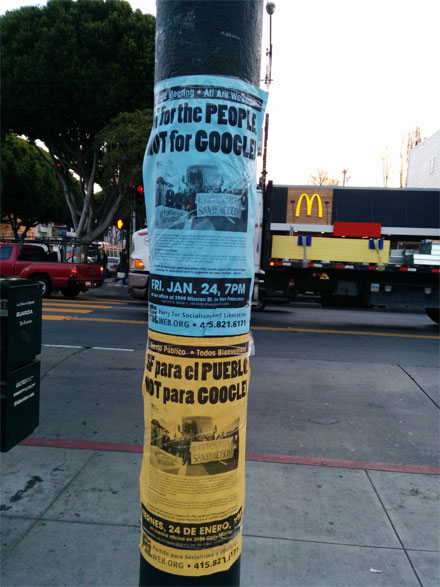

Though the pressure on housing prices comes from more places than just the tech boomers, Mayor Lee’s identification with the tech companies has made it a political necessity for him to address housing affordability photo: john zipperer

HELP FROM WASHINGTON

At least one part of the plan almost immediately got a boost from the Obama administration. On Jan. 23, the mayor’s office announced that the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) had approved the city’s plan to leverage $180 million in private equity and other new sources of funding to rehabilitate as many as 4,584 of San Francisco’s public housing units. San Francisco Housing Authority Commission President Joaquin Torres said HUD’s approval was critical to the effort to improve living conditions “and to preserve the existing affordability for the over 31,000 seniors, families, children, and individuals who call San Francisco public housing home.”

Mayor Lee said the plan “allows us to renovate public housing without displacing existing tenants,“ something that has not always been the case in other cities that have done large-scale reform of their public housing. In Chicago, for example, since 2000, thousands of residents were moved when the city tore down its infamous high-rise public housing estates and replaced 25,000 units with low-rise new and rehabilitated mixed-income units spread throughout that city. Like the redevelopment plans in Chicago, New Orleans, New York, and elsewhere, San Francisco’s strategy involves partial privatization of the housing stock and services, in recognition of the lack of funding at Torres’s agency to carry out the rehab projects on its own.

MAKING IT WORK

For the mayor’s plan to be a success, for it to be a bold success, the city of San Francisco will need to focus on getting as close to 30,000 affordable units newly built. With the mayor’s stated intent of moving much of the cost from the city to the private developers, that means it will be even harder for the developers to make money on the projects. So the best thing the city can do is make the permitting and regulatory side of the process much easier, and that risks poking the beast that is citizen activism, in which everyone is entitled to a vote on whether a project gets built.

Some critics have argued that such changes should be made across the board, and for good reason: Those baked-in costs of doing real estate business in San Francisco are also inflating the prices of the market-rate housing. If Lee’s plan comes to fruition in a form close to what he has proposed, he will be addressing the pains of both market-rate and affordable housing developers at the same time.

But if investors — large or small — think now is a great time to get into the affordable housing business, they should be cautious. Affordable housing development is very complicated, usually involves many layers of subsidy and other funding, and many if not most of the people and companies involved in it are in it for moral reasons instead of profit. Even small affordable housing developments can involve tricky negotiations on deadline with public and private providers of financing, loan guarantors, bond underwriters, and others. It is not for the faint of heart, though having a heart helps.

Beyond the political balancing act of Mayor Lee, all city leaders are facing a challenge. That House Hunters stockbroker who paid for an expensive condo in the city therefore also helped out the city budget with the real estate transfer tax and other fees associated with real estate deals. He is also likely to be spending more money in San Francisco than if he had bought a place in San Jose or Atherton, and that helps jobs, local businesses, and city tax coffers.

In a series of articles in the Examiner at the turn of the new year, Dan Schreiber looked at the effects of the city’s continued growth. Even with the boom-and-bust cycles of California and especially the Bay Area, the trend has been and will continue to be more people in these 47 square miles of San Francisco. “The population of roughly 825,000 in 2012 will have steadily increased to a milestone by 2032, when a projected 1 million people will make their home inside city limits, according to an upcoming report from the Association of Bay Area Governments,” Schreiber wrote. “By 2040, the report speculates that the growth rate will begin to level out at 1,085,700.”

So if Mayor Lee and the current supervisors don’t get it right with their current attempts to address the problem of affordability during an economic boom, they will be postponing the resolution until their successors deal with it, at which time the population will be even larger, the housing stock even older, and available inventory even less affordable.

Lee wasted no time in demonstrating that affordability will be a continuing focus. Just a week after his State of the City speech, he couched his praise of new employment numbers (showing that San Francisco’s unemployment is the third-lowest for any county in the state) by noting that the “robust economic recovery creates new revenue to fund vital city services, and it allows us to tackle the significant affordability challenges that still face working- and middle- class families in our City. That’s why we must continue to pursue an aggressive affordability agenda to build 30,000 new homes by 2020, invest in transportation and education, and attract and grow good jobs for all San Franciscans.”

He is on-message.