This Back Story is a paean to an old friend, Jimmy Lyons. His name may not resonate with some of you unless you have attended the Monterey Jazz Festival. Jimmy was the founder and general manager of this premiere jazz event, and my best buddy until he died in 1994. He deserves remembering. He was a giant in this city that has had many giants. And he was responsible for adding an important dimension — a starburst of focus — to my life.

If it weren’t for Jimmy Lyons, my Telegraph Hill neighbor many blue moons ago, I would not have enjoyed friendships with Duke Ellington, Dizzy Gillespie, Paul Desmond, John Lewis, Charles Lloyd, and other extraordinary artists. Jimmy sharpened my appreciation for jazz and those who created it.

THE JAZZ LIFE EMBRACED

Here’s how all of that happened, how I embraced the jazz life.

Before I met Jimmy, I was what might be termed a casual jazz fan. I enjoyed the big swing bands, and the inventiveness of small jazz groups — say, the Modern Jazz Quartet — interested me in an intellectual, albeit finger-snapping manner. I even attended the first Monterey Jazz Festival in 1958, but more as a social occasion than as a devotee of the music. Then one day in the early 1960s, I met Ralph J. Gleason, the incomparable jazz critic (and later also rock ‘n’ roll critic) for the San Francisco Chronicle. Gleason and I hit it off. To me he was a god who knew everything there was to know about the dynamics of the hipster life. To Gleason I was an eager acolyte. Soon he introduced me to Jimmy Lyons and suddenly I had a job as publicity man for the Monterey Jazz Festival.

When Jimmy hired me, the first thing he asked me to do was to fire my predecessor, Grover Sales Jr. Jimmy, always nonconfrontational, I was soon to learn, didn’t have the stomach for it. Actually, Sales was tiring of the job and really wanted to write about music rather than publicize it — a stance I adopted many years later. But back to Jimmy.

James L. Lyons was born in Beijing, China, in 1916 of Presbyterian missionary parents. The family moved to Cleveland in 1922. Early on Jimmy decided on a radio career. He wanted to be a disc jockey and, “That’s how I got into this strange but wonderful jazz life,” he told me once.

JAZZ JUBILEE AND DISCAPADES

After his schooling in the Midwest and in Southern California, where he attended college, Jimmy Lyons became a radio personality in Santa Ana and soon was into jazz. His eagerness caught the attention of big band stylist Stan Kenton, and he became Kenton’s remote announcer from the radio station, when the band played nearby in Balboa Beach. Jimmy was leading the good jazz life — playing the music he wanted to hear and hobnobbing with visiting jazz artists.

Then Jimmy was drafted into the army (there was a war on, you will remember). With his radio background, he was assigned to the Armed Force Radio network, and for three years produced the wildly popular jazz program, Jubilee. Again, he booked the artists he wanted to hear. That’s how he met Dizzy Gillespie, Miles Davis, Milt Jackson, Lester Young, Charlie Parker, and other household jazz names. In the 1940s, out of the army, he moved to San Francisco and became a late-night deejay on KNBC, a strong station heard on the Pacific Coast from Canada to Mexico. Jimmy Lyons was in the jazz catbird’s seat and his show, Discapades, was an outpost of modern jazz.

A LOVE AFFAIR WITH THE MONTEREY PENINSULA

Dave Brubeck credited Jimmy with helping to establish his group. One night Jimmy introduced Brubeck to a young alto saxophone player from San Francisco State University named Paul Breitenfeld. The youngster took the name Paul Desmond and became an integral element of the Brubeck sound.

My friend, Chronicle photographer Peter Breinig, liked to say he played a major role in the creation of the Monterey Jazz Festival. Breinig became a buddy of Jimmy Lyons. One weekend he was going to visit his parents in Monterey. He suggested Jimmy go along for the ride. It was Jimmy’s introduction to the Monterey Peninsula, a lifetime love affair. Jimmy moved to Big Sur and ran the general store there. On weekends, he drove to Monterey and became a jazz-playing disc jockey on a local radio station. Soon he was conferring with Gleason about launching a jazz festival. Today, the Monterey Jazz Festival is the oldest continuous event of its kind, and arguably the premier jazz festival of the literally hundreds around the world.

INTERACTING WITH THE JAZZ ROYALTY

And that’s how I caught up to Jimmy and he became my best friend. At first I was amazed at the association. Am I really meeting all of these people? I asked myself. Having a drink with them? Occasionally smoking a joint with them? Dining with them? Talking about jazz with them? Gradually, I came to accept it. Jimmy included me in the social interaction with the jazz royalty of the time.

We both lived on Telegraph Hill, Jimmy with his wife, Laurel, in a small apartment on Alta Street overlooking the Filbert Steps, I, on the Greenwich Steps, a couple of hundred yards away by crow flight. Every morning Jimmy and I greeted the day by stepping out on our decks — with a good sightline between us — and talked to each other by telephone. Sometimes Jimmy would wave a tumbler of scotch whiskey at me by way of a greeting. We hung out together.

DIZZY, DUKE, AND DESMOND

When they were in San Francisco, many of Jimmy’s jazz artist friends visited his small apartment. I was invited to drop by, and those occasions were priceless. One night Dizzy Gillespie — a wise and articulate man who loved to play the jokester — was at Jimmy’s. Dizzy said his next stop was Miami for a concert. He added, “It may be your ‘ami’ but it ain’t my ‘ami.'”

Duke Ellington came to town. Jimmy told me to rent a nice car, pick up the Duke at the airport, and take him to City Hall, where he would receive the keys to the city. I got a white caddy convertible, and took my assistant, Vicki Cunningham, with me. Duke was delighted. We put the top down. Vicki, a blonde bombshell (as it was O.K. to say in those days), drove. Duke rode shotgun. I rode in the back.

Paul Desmond was a frequent visitor to the small apartment on Alta. And there, Desmond, Jimmy, and I drank very cold, straight-up martinis. When Desmond died in 1977, Breinig, a fine pilot with a Piper Cub, flew Jimmy, Paul’s ashes, and a shaker of martinis, down over the Big Sur coast. I was invited but couldn’t make it. By prearrangement with Desmond, who had been ill for some time, Lyons and Breinig took a sip in honor of their (and my) friend. Then Breinig flew low, banked the airplane and Jimmy threw Desmond and the martinis out the window. The wind was wrong and Desmond and the martinis blew back into the cabin. I still regret not being there.

ALL-ENCOMPASSING PASSIONS

Over the years I admired and was befriended by many of the greats — Clark Terry, Cal Tjader, Gerry Mulligan, Roy Eldridge, Erroll Garner, Jon Hendricks, Ornette Coleman, John Handy, and Charles Lloyd come to mind.

Most of the great jazz artists from the Jimmy era I was privileged to know as friends are now gone. Of the few who remain, I’m still in touch with John Handy, and Charles Lloyd and I are close friends who meet frequently and enjoy each other’s company.

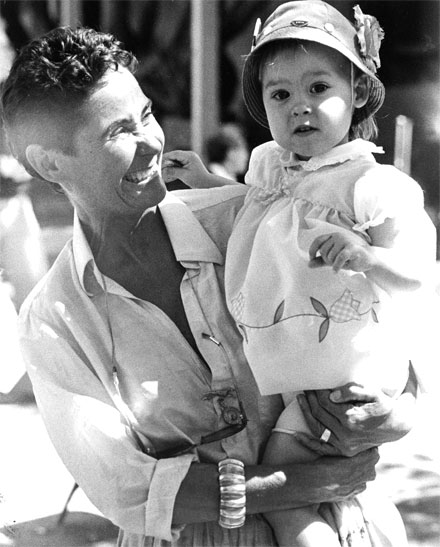

Jazz and the Monterey Jazz Festival were, and still are, all-encompassing passions in my life. When my wife, Joan, became pregnant, we decided that if we had a boy his name would be James. If we had a daughter, her name would be Laurel — after Jimmy’s wife (who died last April).

We had a girl in those pre-ultrasound days. My kids were brought up listening to the music at the festival. Daughter Laurel attended her first Monterey Jazz Festival when she was just 5 months old. She still attends every year. Son Mike became a concert sound engineer. Son Jeff plays jazz guitar. Nepotism at its finest.

Jimmy Lyons was my best friend; I enjoyed his presence in my life and he enjoyed my presence in his. Jimmy was my conduit to the music and to many of its artists I love to this day.