More than 60 works on loan from the museum of Fine Arts in Boston comprise the exhibition “Tattoos in Japanese Prints” at the Asian Art Museum, on display through Aug. 18. The woodcuts are what remain of the popular art of urban life in Japan, specifically 19th-century tattoo culture.

MARTIAL ARTS INSPIRATION

An estimated 45 million Americans have at least one tattoo. Scholars speculate that early tattoo artists may have also been woodblock cutters from the printing industry. “By putting the aesthetic genius of Japanese printmakers on full display, this exhibition underscores how popular culture of late Edo period Japan continues to influence how we express ourselves today,” says Jay Xu, Asian Art Museum director and CEO. Many of the popular subjects of this time — lions, eagles, peonies, dragons, giant snakes, swords, and fierce figures like the Buddhist deity Fudo Mayoo remain part of the lexicon of today’s Japanese tattoo art.

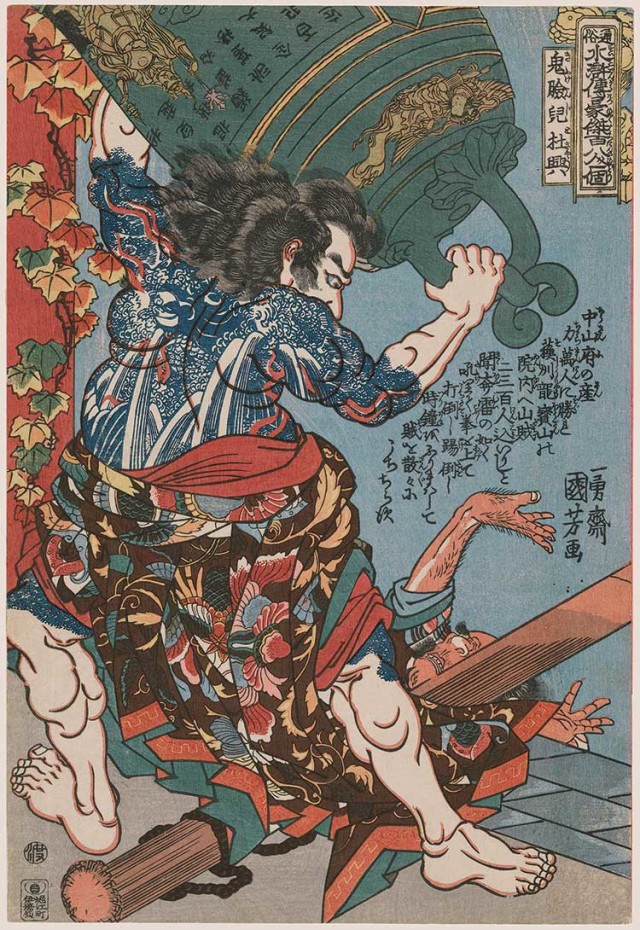

The exhibition traces these designs to a famous set of prints by Utagawa Kuniyoshi (1797–1861) in a series that was inspired by a popular 14th-century Chinese martial-arts novel. Kuniyoshi sought inspiration from the famed “Water Margin” tale, which was published in Japan between 1757 and 1790, a series focused on hero-bandits. His woodblock print Du Xing, the Devil Faced from the series One Hundred and Eight Heroes of the Popular Water Margin (1843–47) is an example of the vibrant, colorful possibilities of this medium in its storytelling and preservation of history. The woodcut Onitsutaya Azamino and Gontaro, a Man of the World (1798–99) by Kitagawa Utamaro shows the process of a tattoo’s creation, a hand pushing ink under the skin with needles.

LINKED TO KABUKI THEATER

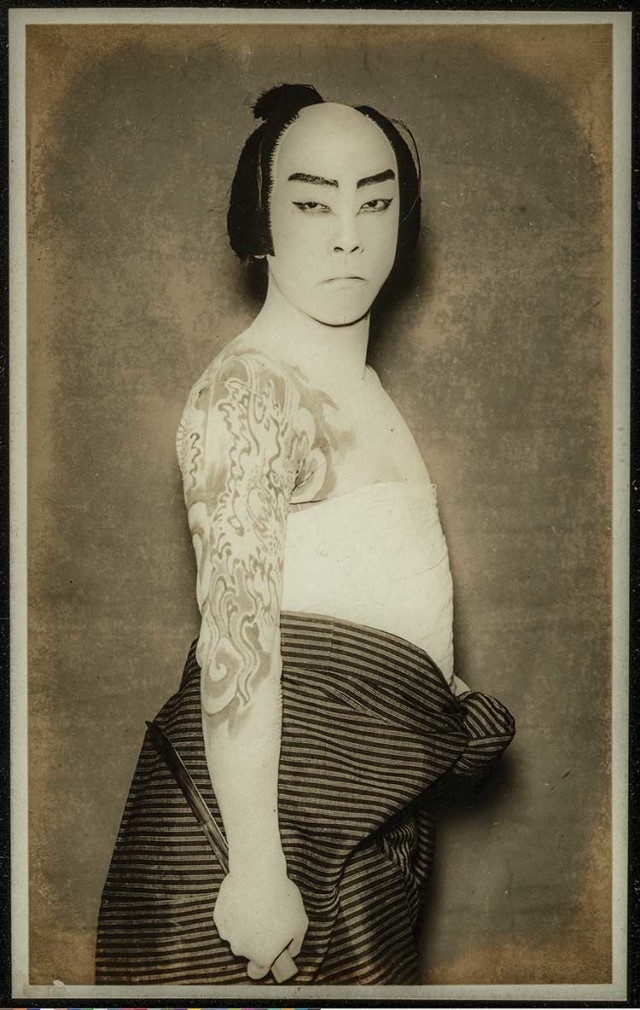

The popularity of tattoos was closely linked to the kabuki theater, Japan’s popular live-action dramatic form. Heroes in popular Kabuki plays were represented in woodblock prints sporting elaborate tattoos. Emblems of bravery, valor, and strength combined with the cult of celebrity are reflected in works like Actor Otani Tomoemon V as Danshichi from an untitled series of actor portraits (1869) by Toyohara Kunichika (1835–1900). Several prints feature surprising gender-bending and fantasy elements of kabuki that highlight the whimsical nature of this genre. Kabuki disallowed female performers on the stage, so cross-dressing was standard in the genre. Also, real-life actors were never tattooed. In performances, they wore painted tattoos or close-fitting garments decorated with tattoo designs. Kabuki Actor, a photo from the 1920s, shows an actor with painted tattoos along with his traditional kabuki hair and makeup.

Shi Jin, the Nine Dragoned, from the series One Hundred and Eight Heroes of the Water Margin, 1853, by Totoya Hokkei

TATOO SUPRESSION AND DEMAND

“Tattoos in Japanese Prints” presents examples of smaller-scale tattoo practices of previous centuries; declarations of religious devotion or the inking of a sworn lover’s name, even some tattoos that would not show the complete design until lovers’ hands were joined. Eventually at the beginning of the Meji period, the government outlawed tattoos, thinking they were old fashioned and, in their absence, would create a better worldwide impression preventing ridicule. Tattoos became associated with criminality and the underworld. “With the official suppression of tattoos, artists largely stopped designing prints of tattooed figures. The woodblock prints in this show survive as some of the best documentation we have of real-life tattoos in 19th-century Japan, and arguably they played a role in ensuring that these motifs endured,” explains Laura Allen, the Asian Art Museum’s chief curator and curator of Japanese art.

The increasing availability of exports from Japan through foreign tourism allowed the history of Japanese woodcuts and tattoo art to find its way into other countries. Despite the government’s wishes, foreign demand for Japanese tattoo art persisted. Tattoo imagery continued to be remembered in reissued prints on photographic postcards for the tourist industry, and sometimes inked directly onto visitors (often navy and merchant sailors visiting Japan), which created and sustained a global fascination with — and deep appreciation for — Japanese tattoo designs.

Kabuki Actor, approx. 1920s. Images: © Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

RELATED EVENTS

Several events are scheduled throughout the exhibition:

• A conversation about the past, present, and future of tattoo art, featuring the Bay Area’s most distinguished and world-renowned tattoo artists including Don Ed Hardy of Tattoo City, Junii Shimada of Diamond Club Tattoo, and Mary Joy Scott of Mary Joy Tattoo & Fine Art, moderated by Taki Kitamura of State of Grace (June 13);

• A workshop on the techniques of Japanese woodblock printing, known as ukiyo-e, with artist Tomoko Murakami, where visitors can learn the art of Japanese ukiyo-e techniques and create their own original prints in the process (June 15); and

• A live tattoo demonstration where guest tattoo artists will create original designs inspired by the museum’s collection on live models (July 13).

In addition, three “At the Table” food-related events are also planned. Visit the museum’s website (asianart.org) for information.

Tattoos in Japanese Prints: Tue.–Sun., 10 a.m.–5 p.m. (Thursdays 10 a.m.–9 p.m. through Aug. 29) through Aug. 18, $25, Asian Art Museum, 200 Larkin St., 415-581-3500,

asianart.org

Sharon Anderson is an artist and a writer in Southern California. She can be reached at mindtheimage.com